The natural world faces an unprecedented challenge as we move into the 21st century and scientists are rushing to unlock their secrets. But understanding wildlife is pretty damn hard if you cannot even find them.

Thankfully award-winning team Dr James Cheshire and Oliver Uberti are scientist hunters extraordinaire and can track animal movements on land, sky and even underwater. Whether elusive big cat or microscopic invertebrates there’s no longer any hiding from their technology.

Mountain lions in southern California have become so tame

For thousands of years, tracking animals meant following footprints but now satellites, drones, camera traps, mobile phone networks, accelerometers and even glued barcodes reveal the natural world as never before.

Where the Animals Go is the first book to offer a comprehensive, data-driven portrait of how creatures like ants, otters, owls, turtles, and sharks navigate the world.

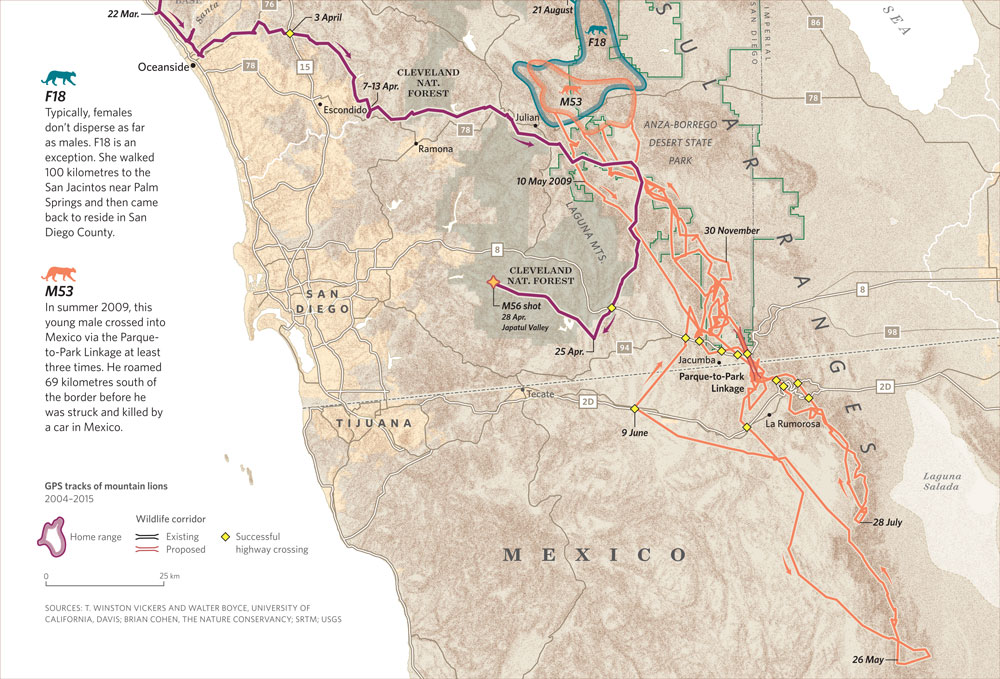

The mountain lions trapped by roads

Mountain lions in southern California have become so tame that one local, known by the very gangster sounding ‘P-22’, has been snapped strolling past the famous Hollywood sign and even visiting the Los Angeles Zoo, where the next day, keepers found the remains of a dismembered koala.

Not great for the koala granted, but 30 years ago P-22 would have been shot dead, today locals are much more comfortable with an apex predator in their neighbourhood. ‘When people see P-22, they treat him like a celebrity,’ says Winston Vickers, a wildlife veterinarian at University of California.

‘As people learn more about these animals – also known as pumas, cougars and panthers – they begin to think of them less like marauders and more like mascots.’

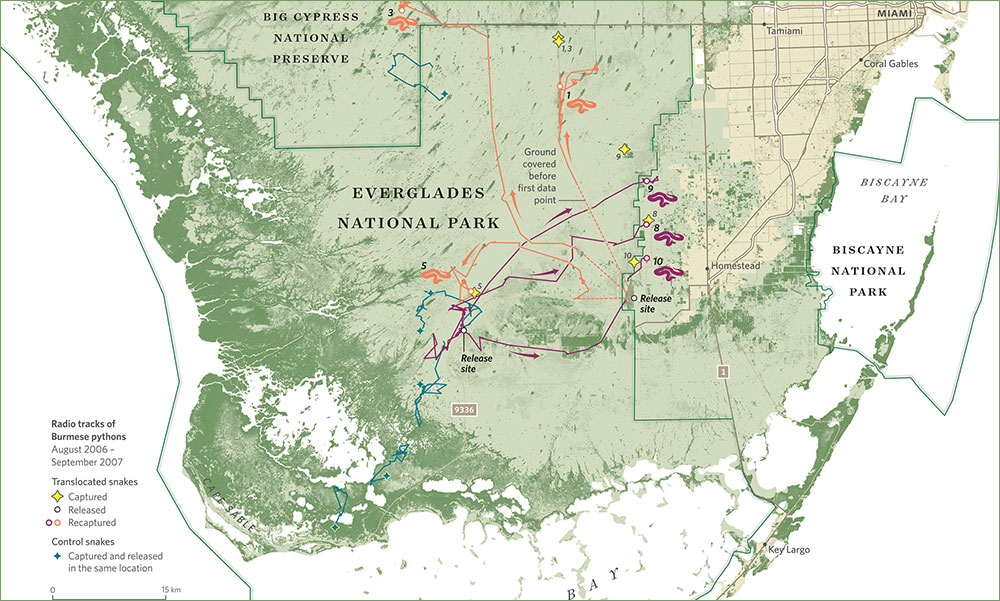

The pythons in the Everglades

It’s not just indigenous wildlife that can be studied. Invasive pythons in the Everglades are estimated in their tens of thousands and Shannon Pittman, a postdoctoral fellow with Davidson College, was curious as to how far they had spread.

It’s not just indigenous wildlife that can be studied. Invasive pythons in the Everglades are estimated in their tens of thousands and Shannon Pittman, a postdoctoral fellow with Davidson College, was curious as to how far they had spread.

She implanted radio tags in twelve released snakes, six where she tagged them and the rest at two locations more than 20 kilometres away.

‘Over the next three to ten months, all six translocated snakes slithered back whence they came, most within five kilometres of their capture locations; they also moved faster and straighter than the control snakes, who had no urgency to get anywhere in particular.’

Not good news, but all data is good data and forewarned is forearmed. With this new information present and future legislation, from national park boundaries to development sites to inventions, can be made with a clearer knowledge and move us towards a better, kinder and more balanced planet.

Click here to buy the book